17 May March 2017 – The Olive Tree Fights Back

The Lexus and the Olive Tree is a book published in 1999 by Thomas Friedman. The book focuses on the power of globalization, symbolized by the contrasting forces of modernizing and streamlining (The Lexus), and culture and identity (The Olive Tree). I distinctly remember discussing this book with a friend back at the time the book was published, and my friend wisely warned me, “Don’t underestimate the olive trees.”

Globalization is an international system that, according to Friedman, began its most recent expansion when the Berlin Wall fell in 1989. At that time the world began transitioning from The Cold War with its walls and divisions to a system of globalization which was inherently more integrated. As Friedman points out in the book, “The challenge in this era of globalization-for countries and individuals-is to find a healthy balance between preserving a sense of identity, home and community and doing what it takes to survive within the globalization system. Any society that wants to thrive economically today must be constantly trying to build a better Lexus and driving it out into the world. But no one should have any illusions that merely participating in this global economy will make a society healthy. If that participation comes at the price of a country’s identity, if individuals feel their olive tree roots crushed, or washed out, by this global system, those olive tree roots will rebel. They will rise up and strangle the process.”

A string of recent events seems to indicate that the olive trees are pushing back against the integration of globalization: Britain’s vote to leave the European Union, the election of Donald Trump, and Marine Le Pen gaining traction in France, to name a few. This push for change can come from a variety of sources: loss of jobs to low cost countries, widening income gaps, and the fear of loss of national identity are some of the likely ones.

If the pendulum has begun to swing away from globalism towards nationalism, this can have important investment implications, especially for global, multinational companies. The Economist recently profiled, “The retreat of the global company.” In this article they pointed out that although multinational corporations account for only 2% of the world’s jobs, they orchestrate the supply chains that account for over 50% of world trade, they make up 40% of the value of the West’s stock markets, and they own most of the world’s intellectual property. Some were built upon the idea that, “global firms, run by global managers and owned by global shareholders, should sell global products to global customers.” This premise is clearly in retreat.

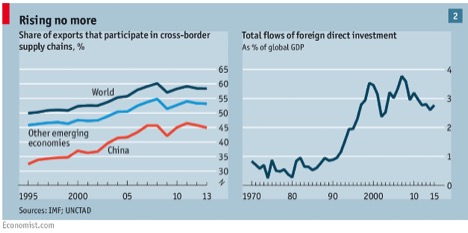

As you can see below, cross-border supply chains have stagnated since 2007 and foreign direct investment as a % of GDP is declining.

This retreat does not mean the end of global multinationals, rather those that survive and succeed will need to be more nimble. There will likely be a focus on localizing inputs and production, to the extent feasible, in the same country as customers. Management teams with in-depth knowledge of customer preferences will also likely be more localized. Some efficiencies and scale advantages will likely be lost, but global companies will likely pay this price to better resonate with customers and avoid being a target of public ire.

Companies may also look to exit areas of the world where they struggle to make a profit. General Motors recently announced that they are exploring the sale of their European division, an area of the world where they haven’t made a profit since 1999. Others could follow suit and focus more exclusively on their home country.

As we look for investment opportunities, we take into consideration a company’s ability to navigate an uncertain political environment, both domestically and globally. From a macro perspective, this political uncertainty widens the range of potential investment returns, which means both upside potential and downside risk are larger. In order to traverse this landscape, we focus on companies that can best steer a ship through seas that can quickly change from calm to turbulent.

Tom Searson, CFA