19 May September 2021 – Inflation Expectations

Stocks have spent the last year and a half climbing a wall of worry. This Wall Street adage speaks to the fact that investors can almost always find something to worry about. In fact, it is when investors are no longer worried that exuberance begins to bubble up, and the next bear market is likely to begin.

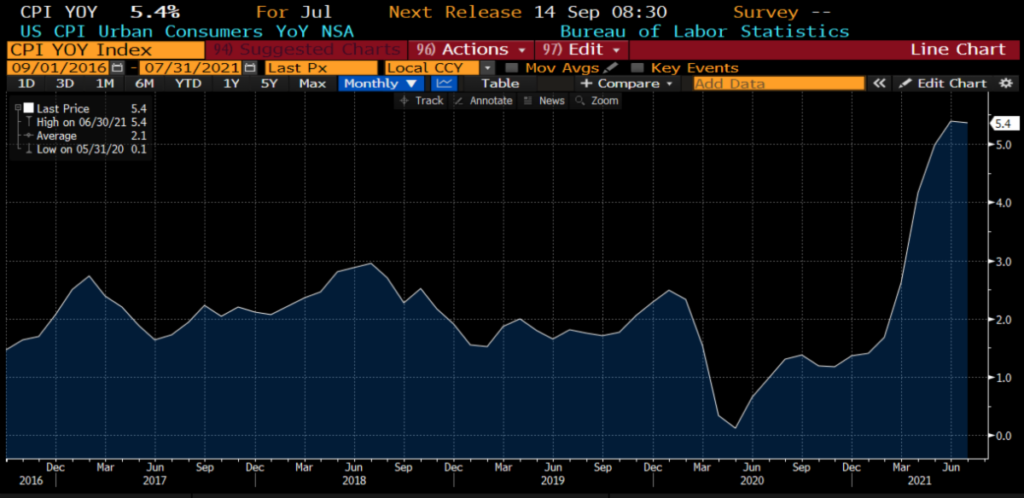

One worry that has ebbed and flowed throughout the year is inflation. On the surface this concern seems well-justified based on the spike in the consumer price index this year.

One factor that magnifies current year readings is base effects. Inflation is measured as compared to one year earlier when prices were depressed due to the initial impacts of COVID. When these base effects are stripped out of the calculation inflation readings are significantly lower, but still higher than the Federal Reserve’s 2% target. Whether these higher readings are transitory and will fall back into the 2% range or inflation will stay persistently high is a hotly debated topic among economists and investors.

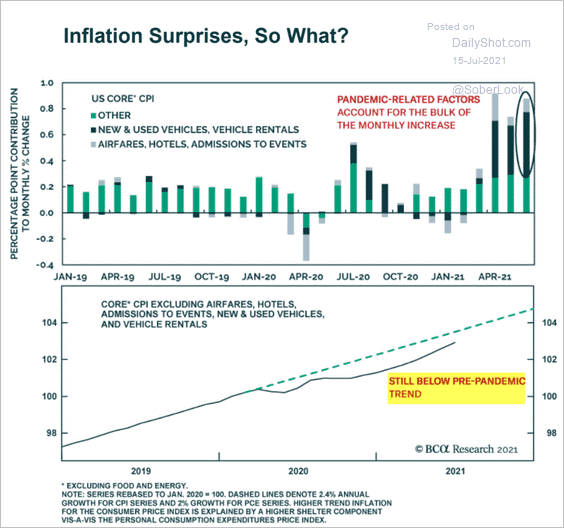

In addition to base effects, a narrow group of durable goods is having an outsized impact on inflation readings. For example supply-chain issues due to COVID compounded by strong demand have diminished the availability of semiconductors. Automobile manufacturers are unable to procure an adequate supply of semiconductors for new autos, which in turn drives up the price of used autos. The chart below shows some of the impact of pandemic-related factors and the level of inflation excluding these factors.

Although pricing pressures from supply-chain issues are likely to abate over time, the historic level of monetary support in response to COVID must also be considered when discussing inflation. The massive amount of liquidity provided to the financial system likely contributed to inflation, but a significant level of the effects were felt in financial assets rather than exclusively in goods and services. The Federal Reserve has telegraphed to the market that they will slow down asset purchases soon, likely later this year. These actions are expected by the market, and if executed as expected, decrease the risk of runaway inflation due to a monetary policy mistake.

Despite the likely trend down in inflation in the near-term, I believe a moderately higher level of inflation than expected could stay in the economic system. We could experience inflation in the 3% range or higher in the near to mid-term future. How would the stock market likely react to these levels of inflation?

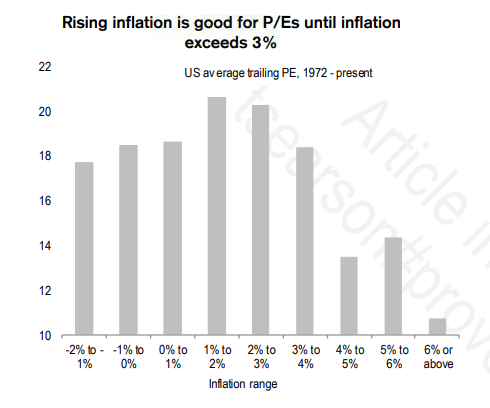

The chart below shows the historic average multiple applied to earnings across different levels of inflation. At inflation levels above 4%, valuation multiples have historically decreased, causing pressure on stock prices.

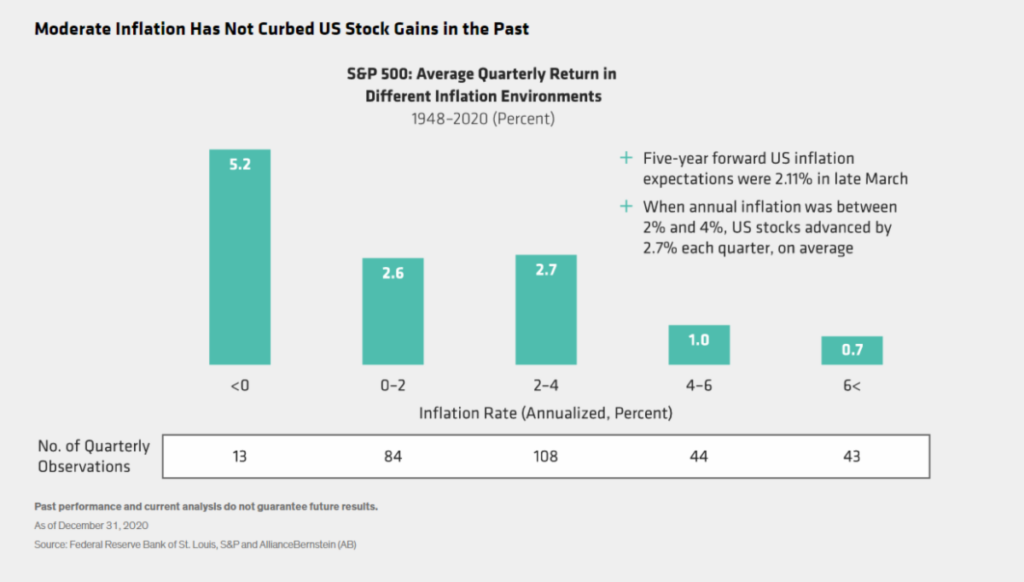

The next chart provides average quarterly returns across different inflation ranges. The conclusion is similar – quarterly returns have been high when inflation is either 0% – 2% or 2% – 4%. Average returns decreased when inflation was above 4%. As a side note – the high quarterly returns during periods of deflation shown in this chart should not be a focus due to the small sample size and upward skew from recession recoveries in the late 1940s and early 2009.

The Federal Reserve is targeting 2% inflation, while allowing for some periods above 2% to make up for past shortfalls to the target. Historical data shows the market could perform well even if inflation remains higher than target – in the 2% to 4% range. So how could we end up with inflation rising more significantly to 4% or higher? The 1960s provide one possibility.

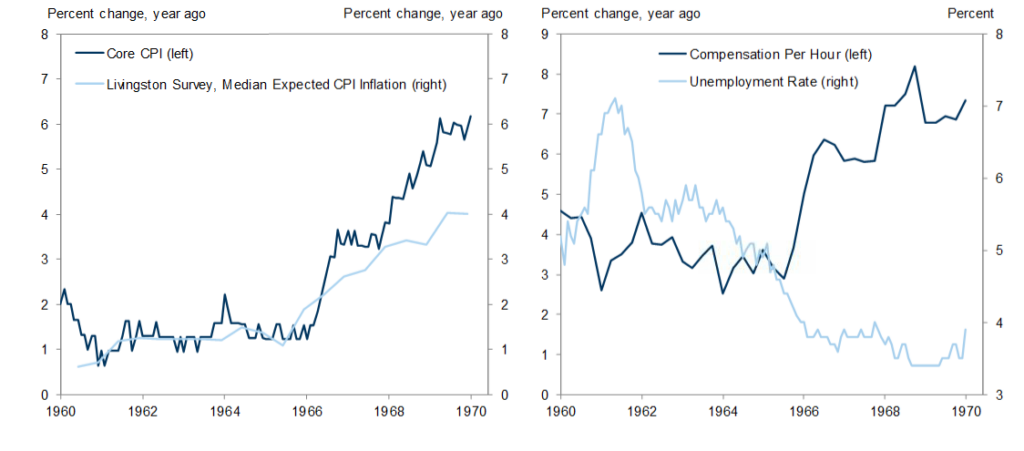

The chart on the left below shows low inflation of 1% – 2% from about 1960 – 1966 before increasing to roughly 6%. The chart on the right shows wage growth of 3% – 4% during the low inflation period. Worker productivity explains why 3% – 4% wage growth can result in 1% – 2% inflation. But as wage growth increased to 6% – 8%, a wage-price spiral ensued. As workers receive higher wages, demand for goods and services increases, causing prices to rise. As prices rise, workers demand higher wages to maintain purchasing power, and a perpetual loop begins.

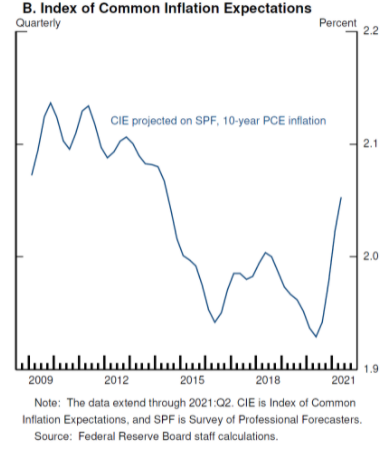

Since this episode in the 1960s, economists have focused on inflation expectations as an important variable in monetary policy decisions. The key thinking is that as long as inflation expectations remain anchored, slightly higher inflation does not pose a risk to the economy. But once inflation expectations become unanchored, the risk of a wage-price spiral increases.

Although inflation expectations have increased recently, they still remain roughly 2%.

There are countless known and unknown risks to the market, with inflation being one of the variables in the known category. As we move forward, our team will be monitoring not just headline inflation, but the underlying components, the pace of wage growth, and the evolution of inflation expectations.

Tom Searson, CFA