17 May October 2016 – In Defense of Trade

International Trade & Political Debate

International trade is at the forefront of political debate, and the chorus of protectionists is growing louder. Fueled by the belief that trade hurts United States workers, an increasing number of people have become deeply skeptical of the benefits of trade.

It is widely accepted in economics that global trade lowers prices of goods, lifts wages, and increases growth. According to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, Americans saw choice of products expand by one-third over recent decades. For example, trade is the reason we can enjoy fresh fruits during the coldest parts of winter. A report by the US Department of Agriculture concluded that increased fruit imports make up for seasonal shortfalls in domestic production, which can help lower prices and smooth out price fluctuations in the domestic market.

In addition, the lower prices of goods disproportionately benefits households with lower incomes. A recent study concluded that closing borders to trade would decrease purchasing power of high earners by 28%, but the poorest 10% of consumers would lose 63% of their spending power.

Higher wages can be seen directly by reviewing statistics that show exporting firms pay higher wages than those that only serve the domestic market.

Higher wages, lower prices, and increased selection are great for our nation as a whole, but economists have long known that there are “winners” and “losers” in trade.

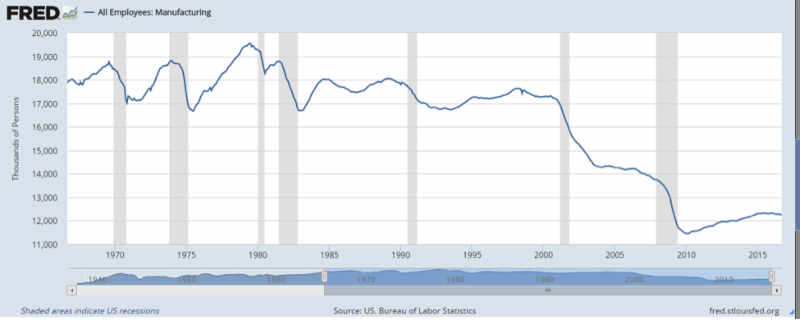

As you can see in the chart below, US manufacturing jobs ranged from 17 million to 19 million until the early 2000s and then began to drop precipitously.

US Manufacturing Jobs: Drop in Early 2000s

China Enters Global Trading System

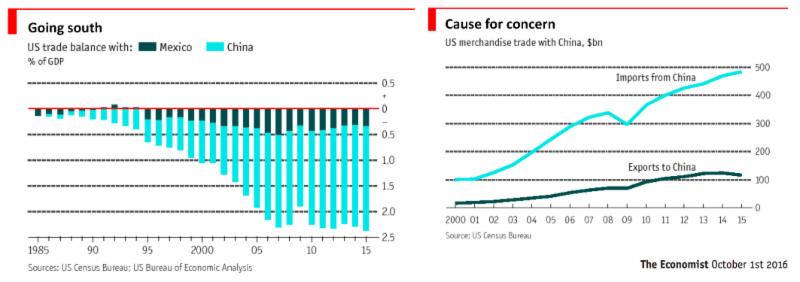

Not coincidentally, China entered the World Trade Organization in 2001 which added 1.3 billion people to the global trading system. The charts below show the explosion in imports from China since this time.

The US lost 5.6 million manufacturing jobs between 2000 and 2010. Despite the explosion in imports from China during this time, a study by the Center for Business and Economic Research at Ball State University estimated that only about 13% of these job losses were due to China. Automation likely accounts for a large part of the balance. It is much easier to place blame on China than on robots, so China and trade in general have become the targets.

Improving vs. Reversing Globalization

The New York Times recently published an interesting article titled, “More Wealth, More Jobs, but Not for Everyone: What Fuels the Backlash on Trade.” A section of this article profiled a steel mill worker in Granite City, Illinois. A father of three children, he had worked at the mill since 1999 and worked overtime to turn his $24.62/hour job into $86,000/year, allowing him to send his children to college. That all changed at the end of the last year when US Steel laid off workers in response to increased steel producing capacity from China. The steel worker that was earning $24.62/hour plus overtime is now struggling to find a job paying $12/hour.

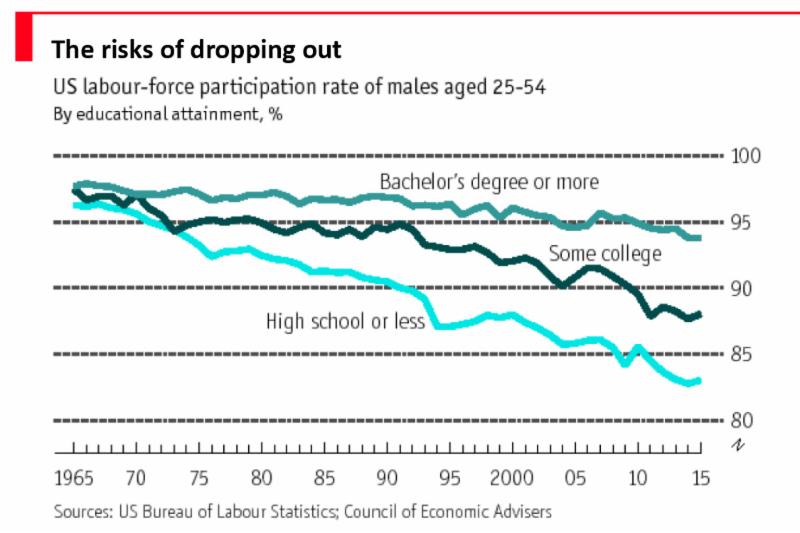

Is it possible to improve globalization rather than reverse it? What can and should we do about those that are hurt by free trade or lose their jobs to automation? The answer, in my opinion, centers on education. The labor force participation rate for those without a college degree has been dropping like a rock for decades, while the participation rate for those with at least a Bachelor’s degree, while declining, is still close to 95%.

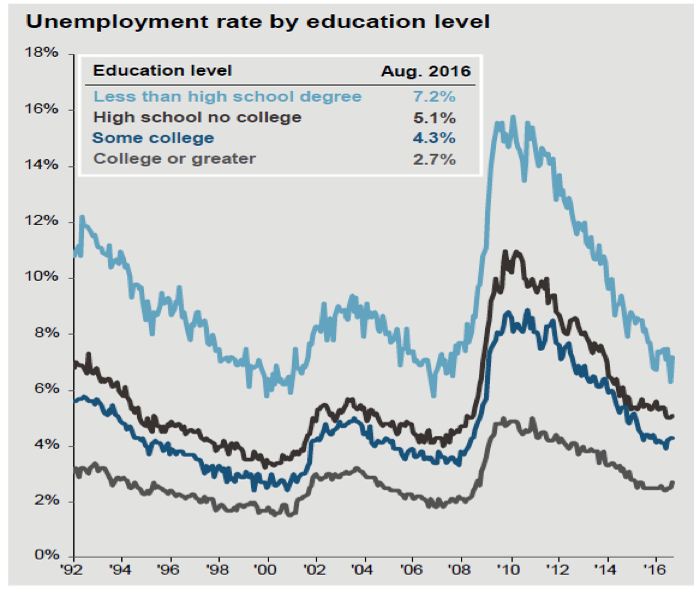

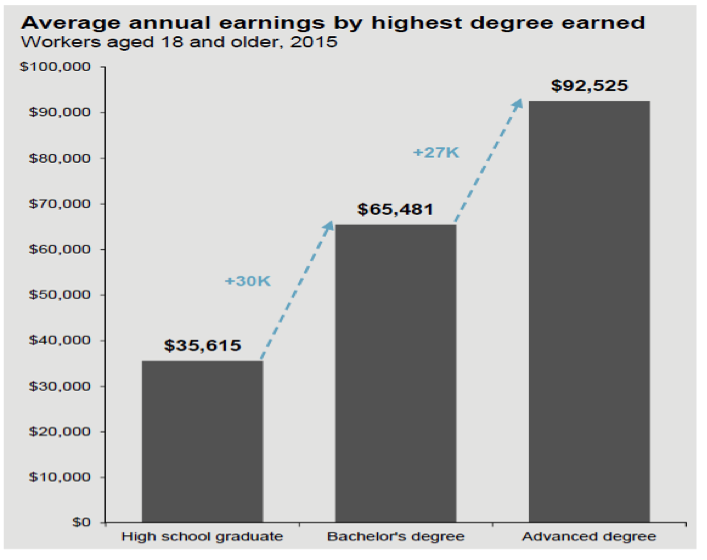

Unemployment rates are also much less volatile for those with a college degree or greater. And, as you would expect, earnings are significantly higher for those with greater levels of education.

Unemployment rates are also much less volatile for those with a college degree or greater. And, as you would expect, earnings are significantly higher for those with greater levels of education.

Education & Workforce Readiness Training

My point is not that everyone should have a bachelor’s degree. Simple economics dictates that the degree will be worth less if everyone has one. However those that do not have a college degree are less likely to be in the workforce, have higher and more volatile unemployment and lower earnings. These individuals should have access to a strong training program that focuses on flexibility to account for the ever-changing employment landscape. The steel mill worker discussed earlier is the stereotypical example, but employment shrinking in an industry due to automation or trade is certainly not limited to blue collar jobs. What if we actually simplified the tax code like both political parties profess as a goal? What happens to the number of accountants that prepare tax returns? Members of the OECD, which is dominated by the United States and Western Europe, on average spend 0.6% of GDP on policies to retrain workers and help them find new jobs, while the US only spends 0.1%. Throwing money at the problem will not fix the issues, but targeted and successful retraining of workers can help economic growth and reduce the backlash against trade.

The managing director of the IMF, president of the World Bank Group, and director-general of the World Trade Organization jointly published an article in the Wall Street Journal recently saying, “Let’s be clear about what’s at stake: Trade is not an end in itself, but a tool for better jobs, increased prosperity and reduced global poverty.” With global growth frustratingly slow, I hope that trade can be seen as a source of faster growth rather than a cause of job loss.

Tom Searson, CFA